Should I stay or should I go?

As European equities surge, investors are rethinking their portfolio allocations

ECONOMICS

Daniel Tuero

One million millions, a thousand billions—or the value of a 67.9-mile stack of $1 bills. All are equally valid ways to represent one trillion dollars: a sum so massive that, put simply, there’s no simple way to put it. Now multiply that by 52. That’s the current market capitalization of the U.S. stock exchange as of April 2025. For investors heavily weighted in American equities, a natural question arises: to what extent is this valuation justified—or at risk of evaporating into what Matthew McConaughey, in The Wolf of Wall Street (2013), famously called “fairy dust”?

Now, how did this come to be? In America, deregulation, constitutional guarantees, reduced corporate taxes, and a spirit of entrepreneurship have spurred hubs of innovation that gave rise to revolutionary companies. Moreover, the U.S. dollar’s status as the de facto reserve currency allowed Americans to borrow more than other nations, enabling businesses to leverage debt and scale at an unprecedented pace.

All the while, the European Union, in the eyes of many investors, stifled the continent’s innovation with decades of excessive regulatory bureaucracy and elevated taxes. Germany’s heavily manufacturing-dependent economy has been hit hard by the surge of low-cost Chinese electric vehicles, which have slashed operating margins for companies like Audi (a subsidiary of Volkswagen). It’s no surprise that building a car in Germany, where workers are better compensated, is more expensive than doing so in China. Yet, with lower production costs in Asia, a lack of European tech innovation, and tepid local demand, the continent found itself, some might argue, stagnating—or at risk of falling behind.

It’s little wonder, then, that the valuation of the so-called Magnificent 7—Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, Nvidia, and Tesla—now exceeds that of the entire European bourse. That sounds outrageous, until you’re asked this question: can you name a European technology company? Chances are, you struggled more than if you’d been asked the same about the U.S.

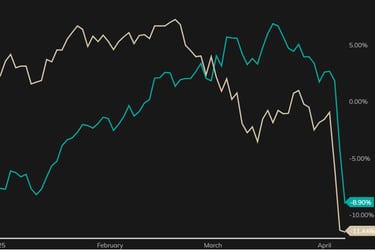

But a recent series of geopolitical developments has begun to aggressively upend that trend. From the beginning of the year to late February, the S&P 500 (a measure of the U.S. equity market) outperformed the STOXX 600 (its European counterpart)—until the momentum shifted, and the latter continued to outperform the former up to the day this article was written. Furthermore, the average P/E ratio—a metric for how much investors are willing to pay for future corporate earnings—for the S&P 500 sits around 21.85, while the STOXX 600 rests at a more comfortable 17.44. Additionally, according to the Wall Street Journal, the predicted return for U.S. large growth stocks is 1.8% annually over the next decade, which would be negative after inflation.

From an investor’s standpoint, it becomes increasingly difficult to justify higher valuations without commensurate returns—particularly in what we might define as a period of high uncertainty, as measured by the VIX Index, Wall Street’s gauge of fear.

S&P 500 (white) vs. STOXX 600 (blue) – 2025 YTD Performance. Credit: Portfolioslab, 2025

This shift began in early February, when the need to renew outdated military equipment—paired with the proximity of the Russia-Ukraine conflict and mounting pressure from the U.S. to meet NATO military spending thresholds—led both Berlin and Brussels to announce increases in government spending alongside a broader deregulation push.

In Germany, the move was driven by Germany’s Chancellor-in-waiting Friedrich Merz, who passed a reform in the Bundestag allowing an exception to the country's characteristically-rigid fiscal policy. Put differently, Germany’s debt levels are significantly lower than those of most comparable economies, with a Debt-to-GDP ratio of 62.9%, compared to the U.S.’s 122.3% and France’s 110.6%. This fiscal headroom allows the German government to raise funds more easily through the issuance of domestic government bonds, or bunds.

Meanwhile in Brussels, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen introduced COMPASS—a framework described as a “new economic-growth strategy that goes easy on climate-change pieties and focuses instead on more private investment.” According to Keynesian economics, fiscal policy in the form of increased government spending and lower taxes can, when executed correctly, stimulate economic growth without necessarily triggering inflation. For investors, both the German and EU-level measures are poised to generate promising effects on the broader economy—and, by extension, resulted in the immediate surge in European equity valuations, which reflect the price of future corporate earnings.

It is worth noting, however, that the defense industry—featuring companies like Rheinmetall and Airbus—benefited the most and likely tilted the index upwards. Auto manufacturers also gained, as they can more easily repurpose their facilities to produce, for example, tanks instead of passenger cars, at a lower cost than other firms.

As of last week, however, concerns over levies imposed by the U.S. on the E.U. have erased most of these gains. It is possible that the U.S. President may demand investment in American defense companies, such as Lockheed Martin or Boeing, as a condition for reduced tariffs—potentially limiting the direct impact of these initiatives on the European economy.

As government spending creates jobs which lead to income for workers, local demand can be reignited. Moreover, reduced regulation and increased support for businesses should eventually spur the emergence of the next generation of European companies. This promising start may well attract investors optimistic about Europe’s future, as well as those rethinking their faith in American exceptionalism and its towering valuations. In all, this decision must be the first of many in a similar direction for a true transformation to take place—but it may just be the spark needed to finally render the Old Continent anew.

Bibliography: