The Intersection Between Latinx Art and Sci-Fi as Resistance

CULTURE

Andre Archilha Anhesini Souza

Can the imagined worlds of science fiction become so relatable that they break through the borders of our own reality? For Latinx creators, science fiction storytelling is not only a form of imaginative escape but a meaningful reflection on dystopian conditions based in real-life experiences. Through themes of control, exploration, and identity, this genre offers a space where past, present, and future can be reexamined. It tests the limits of human existence, the consequences of unchecked technological growth, and the possibilities of redefining social structures. For historically marginalized communities, science fiction has become a way to reflect on the complexities of lived realities shaped by colonialism, imperialism, surveillance, and labor exploitation. These challenges are both historical and ongoing, evolving alongside current debates over borders, digital surveillance, and cultural intolerance. Science fiction, especially when crafted by Latinx voices, provides not only critique but also strategies of resistance, imagination, and recovery. As Antonio Córdoba and Emily Maguire suggest, these narratives often engage with posthumanism ideals by questioning what it means to be human in the face of technological and systemic forces that fragment identity. It is used as means of articulating justice, community, and identity in a world where these values are often overlooked or oppressed.

By blending narratives with artistic and cultural expression, Latinx science fiction emerges as a tool for resistance. This paper argues that Latinx creators use the genre not simply to imagine plausible futures but to expose and challenge systems of control that affect their communities in the present, particularly through border enforcement, technological surveillance, and exploitative labor systems. In the works selected for this analysis, the genre gives form to anxieties about visibility, power, and survival. Whether in visual art, film, or literature, these creators explore what it means to hold onto identity while envisioning something radically better. In support of this argument, according to Matthew David Goodwin from Oxford Bibliographies, Latinx science fiction reflects concerns such as immigration, racism, and language politics. The piece highlights that this genre not only imagines new possibilities for Latinx communities but actively responds to the conditions that shape their present reality. In doing so, these works confront issues of displacement and inequality while proposing new ways to think about identity, citizenship, and belonging.

To explore this argument, the essay analyzes three key works from different media: the film Sleep Dealer, the art exhibition Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas, and the short story Stuntmind, from the literary anthology Cosmos Latinos. Together, these works illustrate how Latinx creators engage science fiction as both a cultural practice and a political intervention.

The film Sleep Dealer (2008), directed by Alex Rivera, is a powerful example of Latinx science fiction that critiques the systems of labor, surveillance, and migration in a technologically advanced but socially divided world. Set in Mexico, the story follows Memo Cruz, a young man from a rural village who dreams of connecting to the global information network. After a tragic drone attack kills his father, Memo escapes to Tijuana, where he discovers a new kind of labor system. There, he finds work in a factory where workers physically plug their bodies into machines that transmit their movements to robots in the United States. This technology allows companies to outsource manual labor across the border without physically admitting the workers. Memo becomes part of this invisible workforce, which plays an important role in the U.S. economy but are physically confined to Mexico. They are needed but are not wanted.

The film’s plot reflects a dystopian world where globalization has intensified inequality. In this way, Rivera’s film imagines a future where labor exploitation has not only persisted but evolved. In a 2010 interview, he explains that the character of Memo was inspired by his own father, who migrated from Peru to the United States in search of work. Rivera notes that he was interested in how technology was simultaneously “making the world feel smaller and more connected” while countries like the United States were “building walls.” This contradiction gave birth to the central idea of the film: a connected but divided world. Rivera’s father had to physically cross borders to find labor. Memo, on the other hand, connects digitally to the U.S., embodying a new kind of immigrant who is integrated into the economy but excluded from rights, visibility, and voice.

Rivera explains that the film is “like a collage,” where some parts look outdated and others appear futuristic. This design choice reflects his political vision of a world where past and future collide, showing how progress in technology does not necessarily bring justice or equity. The aesthetic contrast between old and new reflects the lived experience of many Latinx workers, who are caught between modern systems and historic patterns of exploitation.

Characters in Sleep Dealer represent different aspects of this fragmented reality. Memo is the central figure of resistance and survival, while Luz, a writer who documents Memo’s memories and sells them online, represents the commodification of personal experience and the dynamics of intimacy in a reality highly influenced by digitalization. Rudy, the drone pilot who unknowingly kills Memo’s father, symbolizes the dehumanized function of technology in warfare and surveillance. Each character is affected by technology in ways that reflect broader systemic issues, from border militarization to data capitalism.

Ultimately, Sleep Dealer critiques a future that feels uncomfortably similar to the present. It portrays a world where immigration no longer requires physical movement, where labor is extracted through digital means, and where human connection is diminished and replaced by machines. As Rivera suggests, this is not just speculative fiction, but an amplified version of what already exists. The film’s visual strategies, character arcs, and narrative structure back a major political argument: that being seen, heard, and valued still depend on power structures. Through Memo’s journey, Sleep Dealer challenges the audience to consider how science fiction can reveal the hidden systems that shape labor and identity in our globalized world.

The Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas exhibition explores how Latinx artists use science fiction to respond to histories of colonization, political violence, and cultural displacement. Rather than focusing on traditional science fiction themes like outer space or alien contact, the exhibition reimagines the future as means of criticizing real historical events. In other words, the featured works approach science fiction not as fantasy, but as a tool to critique real conditions and to imagine new ways of existing. By engaging with both local histories and global imaginaries, the exhibition reveals how science fiction can become a language for reclaiming identity and challenging dominant power narratives.

One of the most memorable works in the exhibition is Tropical Mercury Capsule by Simón Vega (Figure 1, 2010). Built between 2010 and 2014 as part of his Tropical Space Proyectos series, the sculpture reimagines Cold War space technology using everyday materials. The shape of the piece is based on the Mercury space capsules used by NASA, but instead of advanced metals and polished surfaces, Vega builds his version out of things like common metal, cardboard, plastic containers, and wood. It is not meant for space travel but rather shows how people in poor communities build things to meet basic needs with limited resources.

The capsule is surrounded by familiar objects like plants, bricks, a cooler, and construction tools. Together, they satirically resemble a scene that feels closer to a Third World scenario than a technological prototype. The object is broken, showing bolts, wires, and tape holding it together. This design contrasts the expected aesthetic of the original space capsule with the everyday efforts of those who work with discarded materials. Instead of romanticizing technological advancements, Vega highlights how people respond to limited access by creating their own versions of the future, reflecting a political reality shaped by Cold War influence and economic turmoil.

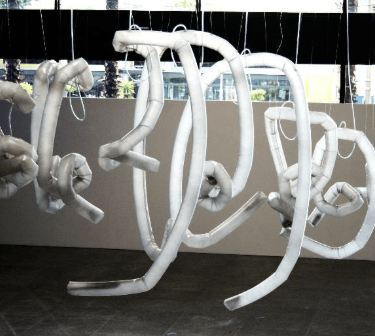

A second work from the Mundos Alternos exhibition that explores the dynamics between human identity and technological advancements is Organic Arches by Chico MacMurtrie (Figure 2, 2014). While Vega’s work is based in historical references to Cold War policies, MacMurtrie’s installation focuses on the relationship between bodies, machines, and space. Made in 2014 with his Brooklyn-based collective Amorphic Robot Works (ARW), Organic Arches consists of inflatable fabric structures suspended from the ceiling. Powered by pressurized air, the arches expand and contract in a slow, rhythmic movement. The result of this installation is a soothing environment, as if the room was breathing, suggesting a future shaped not by rigid control, but by interaction, uncertainty, and fluidity. Unlike traditional science fiction that frames artificial intelligence or robotics as threatening, this work imagines technology as something welcoming, dynamic and in dialogue with the space it is installed.

Visually, the piece replaces the usual metal and sharp edges of a typical technological prototype with a soft sculpture made of high-tensile, Tedlar fabric tubes and pressurized air. The repeated inflation and deflation of the forms create a quiet choreography that feels both mechanical and human. This blending of movement and form challenges the usual separation between organic and artificial life. Organic Arches invites viewers into a space of mutual presence and harmonic coexistence. The most interesting aspect of this work is that it raises a unique perspective of science-fiction through Latinx lenses, by showing how artists may also use science fiction not only to critique the systems that shape their realities but also to offer other ways of imagining movement, interaction, and identity.

Organic Arches becomes a form of resistance by rejecting the idea that technology must always serve power or control. Instead of presenting machines as threatening and dominant, the piece imagines a future where technology is responsive, friendly and an agent for human needs. It opposes the usual association of progress with force or efficiency and offers an alternative vision rooted in harmony. By inviting viewers to participate in this space, the work challenges the idea that the future must be fast, hard, or inaccessible. It offers a slower, more open and optimistic point of view of how people and might move together through space.

Both Tropical Mercury Capsule and Organic Arches explore how Latinx artists imagine the future through science fiction, but they do so with different approaches to technology and hope. Vega’s work presents a critical view of technological progress by showing a destroyed version of a space capsule built from discarded materials. It reflects how people in poor communities respond to exclusion by creating their own versions of progress. showing how survival and creativity can be acts of resistance. On the other hand, MacMurtrie’s Organic Arches presents a more peaceful and hopeful view of technology. His work imagines machines that move gently with their surroundings and interact with people in a welcoming way, suggesting a future where technology supports harmony. While Vega focuses on rebuilding from scarcity, MacMurtrie envisions a soft utopia based on connection and trust.

Turning to literature, Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain presents a textual dimension of the same political and cultural concerns explored visually in the previous works. The stories in the collection show how Latin American authors have long engaged science fiction as a space to address identity, language, memory, and systemic control. For instance, Stuntmind by Braulio Tavares, investigates the psychological effects of alien contact and mental colonization. The unnamed narrator, formerly part of a group known as “stuntminds” trained to endure mental contact with an alien species, is now installed into the body and public persona of Roger Van Dali, a famous actor who was used for publicity during the early stages of the alien “Contact.” After the process left Van Dali mentally destroyed, the narrator inherited his role and surroundings but not his sense of self. He now moves through luxurious spaces haunted by confusion, fractured memories, and the traces of another man’s public life, embodying the consequences of being used and discarded by a system that disregards identity.

After the alien Contact, the narrator is placed into a life that was never his, surrounded by people who treat him as if he were someone else. He is expected to follow routines, uphold a certain image, and participate in a reality that no longer reflects who he is. This tension between who he is internally and how others perceive him reinforces the idea that identity can be socially constructed and maintained through habit and repetition. Even his sense of daily life is built around performance rather than choice. The story suggests that control does not always come from force or surveillance but can also come from social pressure to maintain appearances, even when personal agency is lost.

The story explores how systems of control operate by fragmenting thought, memory, and identity. The narrator is no longer fully himself, as his sense of self is displaced and he becomes nothing more than a vessel for alien communication. By demonstrating this exploitation, Tavares shows how even the mind can be occupied, mined for value, and abandoned. Stuntmind adds a final layer to the broader exploration of Latin American science fiction as a form of critique, exposing how progress and knowledge can mask disempowerment and oppression.

Latinx science fiction does more than imagine distant futures. It creates space to expose and challenge the structures that shape life in the present. Across films, visual art, and literature, the works examined in this essay include Sleep Dealer, Mundos Alternos, and Stuntmind, each of which challenges the dynamics of human interaction with technology, while simultaneously questioning power and identity. Through the intense Sleep Dealer storytelling, the installations of Simón Vega and Chico MacMurtrie, and the plot of Braulio Tavares's story, there is a reflection on colonialism, technological control, and systemic exclusion. Science fiction, in this context, is not an escape from reality but a way to see it more clearly, as it becomes a form of cultural memory, political resistance, and speculative hope.

Each of the works analyzed contributes a specific vision of how the future is shaped power dynamics. Sleep Dealer imagines a dystopian economy where labor and borders are mediated through technology, presenting a world that exploits presence while denying belonging. Vega's Tropical Mercury Capsule functions as a satire that critiques the legacy of war and global inequality by transforming discarded materials into a commentary on space exploration and geopolitical exclusion. MacMurtrie’s Organic Arches offers a more hopeful model, where technology is interactive, suggesting that the future can be shaped by cooperation rather than dominance. Tavares’s Stuntmind provides a psychological lens on posthuman life, showing how control can exist not only through machines but also through identity and memory. Together, these works reveal how Latinx science fiction offers a space to imagine different relationships between technology and humanity, as well as means of resistance and expression of minorities.

Figure 1: Tropical Mercury Capsule, by Simón Vega, 2010

Figure 2: Organic Arches, by Chico MacMurtrie, 2014

References:

Antonio Cordoba and Emily Maguire, Posthumanism and Latin(x) American Science Fiction (Palgrave Macmillan, an imprint of Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2023)

Matthew David Goodwin and Ilan Stavans, “Latino Science Fiction.” Latino Studies. Oxford University Press (2016): https://doi.org/10.1093/obo/9780199913701-0112.

Alex Rivera, “Sleep Dealer - Exclusive: Director Alex Rivera Interview” Interview by Paul Christensen, MovieWeb,YouTube. September 23, 2010, https://youtu.be/rb3IykaKRi4?si=KuUiTgG_pRVqXcWy

“Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas” Queens Museum, 2019. https://queensmuseum.org/exhibition/mundos-alternos-art-and-science-fiction-in-the-americas/

Robb Hernandez, Tyler Stallings, Joanna Szupinska, Kency Cornejo, Rudi Kraeher, Kathryn Poindexter, Itala Schmelz, Alfredo Suppia, and Sherryl Vint, Mundos Alternos: Art and Science Fiction in the Americas. (Riverside: UCR ARTSblock, 2017)

Braulio tavares, “Stuntmind”, in Cosmos Latinos: An Anthology of Science Fiction from Latin America and Spain, Andrea Bell and Yolanda Molina-Gavilá (Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press, 2003)