The Market Machine

ECONOMICS

Daniel Tuero

The concept of perfect information, where all buyers and sellers possess complete and accurate knowledge needed to make informed decisions, is a foundational assumption of an efficient market. Though largely theoretical, one real-world system has come closer than any other to embodying this ideal: the stock market. This essay traces the evolving understanding of market efficiency, from its theoretical underpinnings to its behavioral critiques and technological manifestations, and explores the implications for markets and the financial services profession.

Big Bang

In 1970, American economist Eugene Fama published the groundbreaking paper Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work, which earned him the Nobel Prize. In this work, Fama presented extensive evidence supporting the idea that markets are “fully efficient,” meaning that security prices at any given time “fully reflect all available information.”

The implications of a fully efficient market are profound. If all information is already embedded in prices, stock price movements should be entirely unpredictable, eliminating opportunities for arbitrage. In such a world, speculative traders and active fund managers would have little reason to exist.

Behavioral Corrections

Decades later, in 2013, Robert Shiller, another American economist, offered a compelling challenge to Fama’s framework. In his Nobel-winning paper Speculative Asset Prices, Shiller argued that while prices often reflect available information, they are also heavily influenced by human behavior: emotions, social dynamics, and cognitive biases. This lens, known as behavioral finance, takes seriously the psychological foundations of market activity.

Shiller illustrated this with memorable examples: stocks with patriotic names outperforming during wartime, market returns correlating with weather patterns in New York City, and media cycles privileging sensationalism over substance. These patterns suggested that market behavior cannot be reduced to rational expectations alone.

He also introduced the concept of “smart money”, investors who are systematic, engaged, and research-driven, contrasted with others who base decisions on randomly encountered information. The divergence in their behaviors contributes to inefficiencies and speculative bubbles. As Shiller explained:

“When a bubble is building, the suppression of some facts and embellishment of other facts [...] occurs naturally through the decay of collective memory, when media and popular talk are no longer reinforcing memories of them, and because of the amplification of other facts through the stories generated by market events.”

(Shiller, 2013)

Shiller credited John Maynard Keynes, a 20th century British economist, for his almost prophetic insights into behavioral tendencies. Keynes introduced the term “animal spirits” to describe the emotional impulses behind economic decisions under uncertainty. He also described speculative investing as being driven more by expectations of others’ behavior than by intrinsic value. As Shiller observed, “There are some, I believe, who practice the fourth, fifth, and higher degrees” of such speculation.

The Machine Age

In 1982, Jim Simons, a former mathematician and codebreaker, founded Renaissance Technologies, the quintessential quantitative investment firm. Under the banner of an “investment firm,” Simons recruited PhDs in mathematics, physics, and computer science and gave them a singular mission: to build a system that could consistently outperform the market.

They succeeded. Renaissance’s Medallion Fund has posted average annual returns of around 39%. The fund is now closed to outside investors; only employees and select invitees are allowed to participate.

The success of Renaissance signaled a new frontier: data and algorithms could detect minuscule inefficiencies and act on them faster than any human could. This innovation paved the way for high-frequency trading (HFT), machine learning, and artificial intelligence to enter the markets.

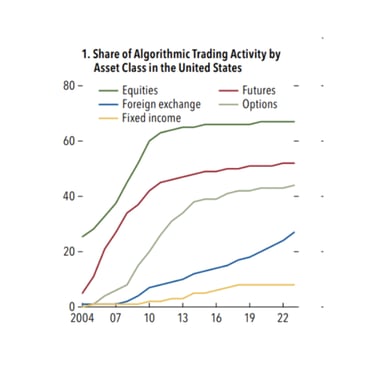

According to the International Monetary Fund, it takes roughly forty-five seconds for high-frequency trading algorithms to respond to the release of Federal Open Market Committee minutes, digesting the content, interpreting its tone, and executing hundreds of thousands of trades in fractions of a second. In the United States today, algorithmic trading accounts for approximately 70% of equity trades and more than half of futures trading.

(IMF, 2024)

Implications of an Efficient Market

At its core, the stock market facilitates the attraction and allocation of resources from investors to businesses. It operates under the premise of a free market and limited liability, guaranteeing investors’ rights to buy and sell securities while protecting them against “the sins of companies.” This combination has proven to be a highly effective platform that enables, encourages, and rewards:

Funding for industries aligned with societal progress. Examples include drug discovery in healthcare, smartphones in technology, and electric vehicles in transportation.

Scaling operations to meet demand and maximize revenues, which in turn creates high-paying jobs and stimulates economic growth.

Fostering competition, which ultimately, and in theory, ensures that consumers have access to the best and most affordable products.

All in exchange for equity, that is, an entitlement to the enterprise’s future earnings or dividends as compensation for the capital provided, the embedded risk, and the incurred opportunity cost. Moreover, this structure can be further enhanced when a company chooses to reinvest its profits, increasing its value and capacity to achieve the objectives mentioned above.

The stock market is the backbone of financial capitalism, a system that, in Shiller’s words, “brought the level of prosperity that we see in much of the world today, and there is every reason to believe that further expansion of this system will yield even more prosperity.”

Both theory and technology have virtually made informational efficiency a reality. However, efficiency is not always aligned with what is desirable for our society. An efficient market may allocate capital to socially harmful industries or short-term profit schemes that, at best, fail to contribute, and at worst, actively harm, the previously outlined objectives of the stock market. These broader trade-offs, which ultimately ripple through the economy, must be assessed by principled investors who can make decisions that maximize returns alongside society, not at the expense of it. Only in this way can the market fulfill its ultimate purpose: to serve as a mechanism for sustainable prosperity by creating true value.

Focusing on the financial services industry, it follows that professionals in the industry must adapt to an era where informational edges vanish, and where principled decision-making and the ability to navigate complex trade-offs become the new source of competitive advantage. Finance professionals must now more than ever become the architects of resilient and responsible capital flows.

Here’s a rundown of what it would look like for professionals in the industry, according to an LLM:

For investment bankers, this means going beyond transactional deal-making to become long-term partners to clients—advising on sustainable growth strategies, ethical capital structure design, and stakeholder impact. For private equity professionals, alpha generation is no longer just about financial engineering, but about building better companies: improving operations, fostering innovation, and aligning incentives with long-term performance. In asset management, the rise of passive and algorithmic investing has placed pressure on active managers to justify fees through unique insights, often grounded in deep research, governance engagement, or thematic convictions such as climate resilience or digital transformation.

As a prospective finance major at Georgetown, a transition towards a more technologically advanced industry seems inevitable. The development and democratization of information and tools such as large language models allow for incredibly rapid information processing, further eroding the competitive advantages of informational efficiency. The competitive edge in the financial industry is shifting away from information processing toward something more akin to strategic clarity and principled decision-making, both elements of the concept of stewardship. Stewardship, defined as the responsible allocation and oversight of capital, demands that investors consider not only returns, but also long-term risks, externalities, and broader societal outcomes. I see technology and efficiency as an opportunity to automate time-consuming tasks while leveraging creative insights that are not opposed to technology, but enhanced by it. Some might think me overly optimistic, but I believe this process could actually bring our societal objectives and high-return opportunities closer together. In a world driven by quarterly earnings, consumer confidence indices, and the next Federal Reserve meeting, I’ve found it useful to step back and remind myself how—and why—it all matters. The efficient market is not the end, it is merely the beginning of a more sophisticated, ethical, and consequential era of financial services.

References:

Fama, E. (1970). Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work. The Journal of Finance.

Retrieved from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2325486?seq=1

IMF. (2024). GLOBAL FINANCIAL STABILITY REPORT. International Monetary Fund.

Retrieved from: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/GFSR/Issues/2024/10/22/global-financial-stability-report-october-2024?cid=bl-com-AM2024-GFSREA2024002

Shiller, R. (2013). Speculative Asset Prices. Yale University.

Retrieved from: https://www.nobelprize.org/uploads/2018/06/shiller-lecture.pdf